HTML

Perspective - (2023) Volume 13, Issue 2

The Significance of Reconciling Medications and Counselling for Patients in Drug Safety Recognized by Pharmacists

Arsalan Elmasry**Correspondence: Arsalan Elmasry, Department of Pharmacy, University of London, London, United Kingdom, Email:

Received: 21-Feb-2023, Manuscript No. IJP-23-94117; Editor assigned: 23-Feb-2023, Pre QC No. IJP-23-94117 (PQ); Reviewed: 14-Mar-2023, QC No. IJP-23-94117; Revised: 23-Mar-2023, Manuscript No. IJP-23-94117 (R); Published: 31-Mar-2023, DOI: 10.37532/2249-1848.2023.13(2).42

Description

Ageing is known to gradually weaken human organs and physical functions, increasing the likelihood of various chronic illnesses, frailty, polypharmacy, and drug management challenges. As a result, the elder population (individuals above the age of 65) forms the majority of patients in ambulatory and hospital care. With the global growth in lifespan, the percentage of elderly individuals will continue to rise. This indicates that the primary patient population in ambulatory and hospital care will age and require more complicated medical and pharmacological treatment.

According to scientific study, the prescription, procurement, preparation, distribution, management, and (self) administration of medications include complicated activities that might result in Medication Related Problems (MRPs), which can cause patient damage. An MRP was defined as an incident or scenario involving a medication therapy that interferes with the targeted health results, either directly or indirectly. As a result, pharmaceutical mistakes are included in the definition. Scientific study also suggests that MRPs rise as a result of substitution policies, medication shortages, or other supply concerns, and that they are particularly common in polypharmacy patients over the age of 65. All of this suggests that hospital pharmacists should pay special attention to drug safety in the elderly. Pharmacists, medical physicians, general practitioners, nurses, midwives, and other healthcare professionals in the Netherlands can report MRPs to the Portal for Patient Safety (PPS) (PPS; earlier named Central Medication Incidents Registration). PPS is a nationwide pharmaceutical incident record that filters, analyses, and assesses MRPs before deciding whether to issue an alert to healthcare practitioners. Moreover, newsletters and other pertinent material are made public on the PPS public online portal. This approach is consistent with the Swiss cheese paradigm, which holds that risk mitigation measures in pharmaceutical care should be implemented at numerous layers rather than just the layer where the error happened or where the error should be avoided in the first place.

The PPS has proved to be beneficial in evaluating MRPs such as anticoagulant drug mistakes, IT difficulties, or problems with automated dosage dispensing. There is yet to be a comprehensive study of any MRP relevant to older persons and (possibly) related to pharmacological product design. The major goal was to examine systematically the MRPs in the public PPS that are important to older persons and for whom certain characteristics in the medicinal product design give opportunity to decrease risk and hence increase medication safety. The secondary goal was to assess the potential implications of MRPs for existing hospital/clinical practice.

In the Netherlands, no ethical approval was required for this investigation. The public PPS does not include any patient-specific information. MRPs seen in regular hospital practice were documented without any reference to a specific patient; rather, only generic features known to the hospital pharmacy were reported, such as an older patient with dysphagia or an older patient on polypharmacy. Hospital pharmacists in the Netherlands recognize the importance of medication reconciliation and patient counselling in drug safety. As a result, following departure from the hospital, the drug regimen is discussed with the patient, and information is adapted to the patient's specific needs. Patients are then offered the option of picking up their medicine at the outpatient hospital pharmacy. However, some drugs, such as pricey oncolytic treatments, can only be accessed through the outpatient hospital pharmacy and not the patient's community pharmacy.

Conclusion

Severely unwell individuals in hospitals may require costly parenteral drugs. However, it should be noted that items with a limited inuse shelflife may need to be thrown if the appointment is cancelled or the doctor believes the patient is too weak to receive the drug. Moreover, low inuse shelflives (e.g., less than 3 h) suggest logistical issues for hospitals. Recognizing that hospital pharmacies can take adequate measures to prevent microbial contamination, it is critical that the user instructions include information on the product's in-use shelflife from a chemical-physical standpoint, and that this in-use shelflife is as long as reasonably possible and not based on a lack of stability data.

Manuscript Submission

Submit your manuscript at Online Submission System

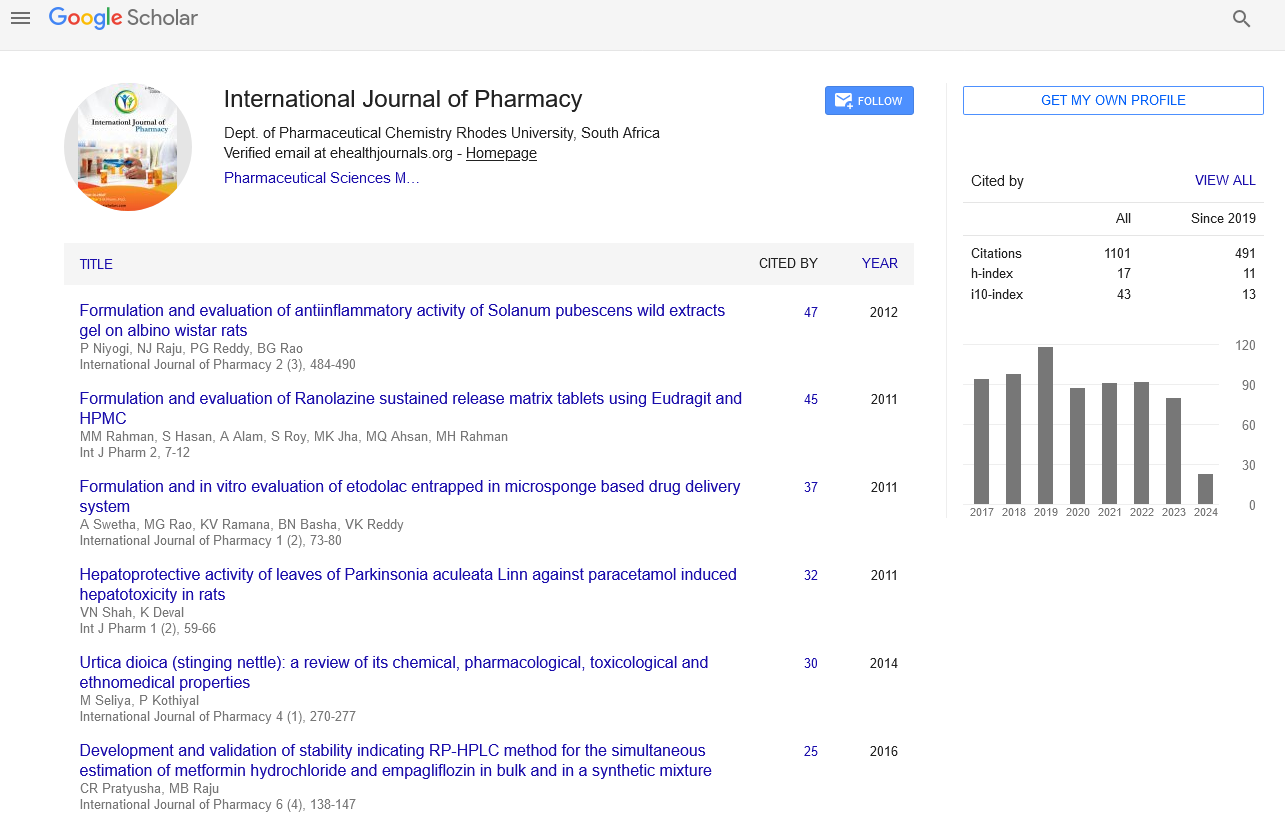

Google scholar citation report

Citations : 1101

International Journal of Pharmacy received 1101 citations as per google scholar report

International Journal of Pharmacy peer review process verified at publons

Indexed In

- CAS Source Index (CASSI)

- HINARI

- Index Copernicus

- Google Scholar

- The Global Impact Factor (GIF)

- Polish Scholarly Bibliography (PBN)

- Cosmos IF

- Open Academic Journals Index (OAJI)

- Directory of Research Journal Indexing (DRJI)

- EBSCO A-Z

- OCLC- WorldCat

- MIAR

- International committee of medical journals editors (ICMJE)

- Scientific Indexing Services (SIS)

- Scientific Journal Impact Factor (SJIF)

- Euro Pub

- Eurasian Scientific Journal Index

- Root indexing

- International Institute of Organized Research

- InfoBase Index

- International Innovative Journal Impact Factor

- J-Gate